PORTFOLIO

Mark Neff

Department of Environmental Science

Critical Thinking and the Nature of Conflict Resolution

I teach environmental policy courses for Huxley College here at Western Washington University, and within that realm my focus is on the way that science interacts with policy processes. Students coming into my classes typically have strong passions for the natural world, and many of them are confident that they know the solutions to the world’s environmental challenges. In other words, they are in roughly the same position I was in after college. My experiences since then have shown me, however, that the world is more complicated and interesting than I had understood it to be. Simultaneous to helping them to develop their knowledge bases and communication skills, one of my main goals as a professor is to help my students understand the complexity that underlies real-world social and environmental problems. If I am doing my job right, students leave my classes less sure that they know how to fix the world’s problems, but better able to critically evaluate their own understandings and recognize the merits of competing ideas. This critical thinking and reflexive self-awareness is the “magic sauce” that – at least in my distorted view of the world – will enable our students to be effective change agents.

"Students coming into my classes typically have strong passions for the natural world, and many of them are confident that they know the solutions to the world’s environmental challenges. In other words, they are in roughly the same position I was in after college".

If I am doing my job right, students leave my classes less sure that they know how to fix the world’s problems, but better able to critically evaluate their own understandings and recognize the merits of competing ideas.".

Any contemporary observer of the news knows that our society is deeply divided on the proper course of action in any number of policy realms. Counter to Enlightenment logic, providing fact-based arguments does not yield policy consensus in these contested realms because our disagreements rarely are rooted in factual misunderstandings. My goal is to ensure that my students understand not only relevant facts, but also the necessarily-limited roles that facts play in policy disputes.

The Limited Role of Facts in Controversy

A personal example will illustrate what I mean. My first position in the environmental field was as a volunteer for a non-profit organization, where I was asked to write a white paper summarizing the science around a wildlife disease management controversy. The group I worked for advocated a less-intensive management approach. A feeding program kept the regional elk herds artificially large and concentrated them in ways that allowed the disease to become widespread among the elk. The answer — I was sure — was to reduce the feeding program since unfed elk do not transmit the disease to one another. Cattle ranchers and some tourism-oriented actors preferred to maintain the feeding program and vaccinate the elk. Feeding accomplished the twin goals of preventing transmission of the disease to regional cattle and ensuring tourist access to large and visible wildlife herds. To my way of thinking at the time, I could contribute toward a resolution by translating the science to better inform these folks. Elk herds that were less-intensively managed do not carry the disease and the vaccine insufficiently effective in elk to control the disease. The science was settled, it justified my policy preference, and others would agree when I summarized the technical information in an accessible way.

I spent months reading the technical literature and took care to distil it in a way that was true to the scientific details yet was accessible to a wide audience. I was proud of the document I produced. The first people I presented it to responded just as I suspected they would: “Well yes, of course. Nature takes care of itself when you let it.” When I offered my summary of the science to those who were not already onboard with the hands-off policy option, however, they argued back. And they had their own peer reviewed scientific knowledge base to draw from. We needed more intensive wildlife management, they were sure, if we were to successfully address the disease.

The disease in question is well understood and affects both domestic livestock and wild ungulates. There were effective vaccines for livestock, but they did not confer adequate resistance in elk. By the logic of science rooted in game management and veterinary science, what was needed was not a decrease in the intensity of management, but rather more frequent and aggressive administration of the vaccine, research to improve the vaccine options, and more direct “scientific” management of the herds.

"My facts were correct, as determined by the standards of peer-reviewed science, but so were theirs."

My facts were correct, as determined by the standards of peer-reviewed science, but so were theirs. My facts seemed to justify minimizing management, and theirs seemed to justify intensifying it. Advocates for each position knew that their preferences were vindicated by science, and those most intimately involved in the controversy were quick to defend their positions by invoking peer reviewed facts. You can manage how effective those conversations were.

As I now know, the dynamic I experienced is a common one. Science didn’t settle the controversy but rather provided ammunition for fact flinging that tends to occur between advocates of opposing positions in social and environmental dilemmas (Sarewitz, 2004). Our preferences diverge because of different underlying assumptions of, for example, what the goals are, what the environment is for, and the proper roles of governments in shaping individual choice and market structures (e.g., Kahan & Braman, 2006). The idea that offering fact-based arguments is how we persuade others of the merits of our preferences is deeply rooted in our culture. Despite its instinctive appeal, it is ineffective. Factual understanding of the world is of course necessary, but it does not compel those who have different goals in a policy dilemma to suddenly agree with our approach. In the wildlife management example, my underlying preference was to restore natural processes and minimize the intensive management of the herds. If I’m honest with myself, I had this goal prior to learning anything about the wildlife disease. Those who preferred more intensive vaccine-oriented management were motivated by the desire to maintain large elk herds accessible to tourists and minimize intermingling of elk with cattle largely for economic reasons. Our disagreement was rooted in divergent goals, yet our instincts were to argue with facts about ungulate epidemiology and ecological processes. Both sides had well-established traditions of scholarship to draw upon as sources for our ineffective rhetorical fact flinging.

"The idea that offering fact-based arguments is how we persuade others of the merits of our preferences is deeply rooted in our culture. Despite its instinctive appeal, it is ineffective."

Once you scratch the surface, most policy dilemmas have a lot in common with the above example. Critical thinking is what allows students not only to be aware of scientific facts surrounding a policy dilemma, but also to understand the limited role that those facts can take in determining the “best” policy option or alleviating disputes. The field of Science, Technology, and Society has over the past several decades created a vocabulary and a set of theories to better understand science and society relationships, but I prefer to introduce these ideas to students via case studies and real-world examples. Once students have examples, I then help them to walk through the theory that explains the dynamics we observe. Below, I’ll describe how I seek to develop students’ critical thinking skills about the roles of science in environmental dilemmas in two of my courses.

"Making better decisions with science requires having critical thinking skills about the strengths and limitations of science in policy processes. Through case studies and theoretical readings, my students and I examine several ways in which actors attempt to mobilize science in service of decision making. "

ENVS 450: Science in the Policy Process

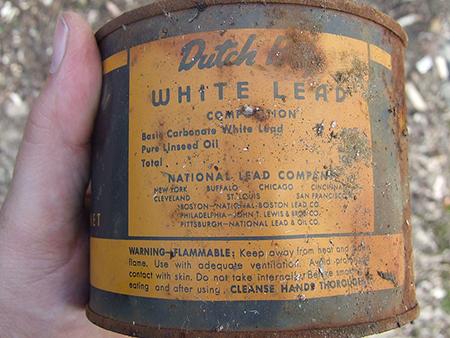

Many of the students in my ENVS 450: Science in the Policy Process course are aware of the endocrine-disrupting effects of bisphenol-A (BPA), an ingredient commonly used in plastics. They have dutifully gone through their collections of water bottles and replaced old ones with new BPA-free ones, and they are shocked to learn that the Food and Drug Administration has not prohibited its use in food containers. That, to my students, is a black-and-white example of a regulatory failure; I prefer to start with a more obvious one: lead. We have known since antiquity that lead is toxic, and we have used it since that time in ways that have ensured that we all have measureable levels of lead in our blood. It was formerly (and still is in some countries) an additive to gasoline, ensuring that it was a widespread air pollutant. We painted our houses with it for decades in this country; US-based paint companies still sell lead-based paint for domestic use abroad (Kessler, 2013). And we built substantial portions of our water supply system out of it and alloys that contain it, a choice that we were recently reminded of as Flint, MI dealt with its devastating water quality problems. We made all of these choices two millennia after Hippocrates described some of the health impacts of lead poisoning (Papanikolaou, Hatzidaki, Belivanis, Tzanakakis, & Tsatsakis, 2005).

I guide my students through a history of the battles over lead regulations in this country (Denworth, 2008, or; Markowitz & Rosner, 2013) to help them to better understand how it is that we came to use a known neurotoxicant so widely that we guaranteed our exposure to it. Part of the story is what students expect: that the lead industry has deliberately sought to muddy societal understanding of lead toxicity. What students do not typically anticipate, though, is that the lead industry has been successful in their efforts in part because we collectively expect science to produce kinds and levels of certainty that it cannot deliver (Collingridge & Reeve, 1986; Sarewitz, 2004). Certainty, scholars of this realm argue, is a function of the stakes at play. If an actor interprets a proposed regulatory decision as costing them money, that actor has every incentive to ask difficult questions about the science: Are there other possible causes of the observed effect? Was the sampling strategy appropriate? Are there other scientific methods that could be used? As the stakes go up, the incentives for actors to ask these questions increase. Scientists are typically willing to oblige by conducting additional research in the effort to reduce uncertainty (Oreskes, 2004).

"Critical thinking about science means recognizing both the strengths and limitations of science. Through case studies and theoretical readings, my students and I examine several ways in which actors attempt to mobilize science in service of decision making."

Making better decisions with science requires having critical thinking skills about the strengths and limitations of science in policy processes. Through case studies and theoretical readings, my students and I examine several ways in which actors attempt to mobilize science in service of decision making. There are examples of successes and failures. By the end of the class students report that they have a renewed optimism that we are capable of making good decisions informed – but not determined – by science, even if they themselves are less confident in what those decisions should be.

ENVS 456: Environmental Governance

Whereas Science in the Policy Process wades into the weeds of the science-policy interface, my Environmental Governance class takes on the related issues of cultural disagreements that underlie many of our environmental and social policy disputes. As a society, we do not agree with one another, for example, on the roles that government should play in our lives and the roles that markets or technical experts in a democracy. But crucially, when we study policy and governance controversies, we focus primarily on technical disputes rather than recognizing that cultural issues are at play and in many ways determine the contours of disputes.

"In Environmental Governance I upend my students’ understandings by providing them not just with scholarship and ideas of the sort typically presented in environmental studies courses, but also with readings that, being rooted in different cultural notions of what a good and just world looks like, directly challenge those ideas. "

In Environmental Governance I upend my students’ understandings by providing them not just with scholarship and ideas of the sort typically presented in environmental studies courses, but also with readings that, being rooted in different cultural notions of what a good and just world looks like, directly challenge those ideas. Savvy students have long noticed that their courses in different departments are operating from different and occasionally incompatible starting assumptions. They learn to don their “economics” hat when they walk into those classes and their “environmental studies” hat when they walk into ours, and so on. What students are learning in these courses does not necessarily fit into a cohesive whole, yet there are few opportunities on campus for them to systematically confront the apparent contradictions. My goal is create a safe and challenging space for those discomfiting conversations. And I do not wait for them to happen; I force them.

"My goal is to create a safe and challenging space for those discomforting conversations. And I do not wait for them to happen; I force them."

Many of the classic thinkers assigned in environmental studies courses lament the destructive impacts of industrialization and technology on the environment. It is uncontestable that many of the environmental challenges that we face today are the products of technology (e.g., air and water pollution, environmental toxicants, climate change), but how to address these problems is not settled. Should we aspire to lessen our reliance on technologies and “live simply so that others may simply live?” Should we move to cabins in the country, à la Thoreau, to reconnect with nature and go off the grid? I ask students to read texts written in that tradition, but then I also assign readings that force them to consider the alternative: That the answer to the problems caused by technology is the further pursuit of innovation and technology, even while recognizing that these techno-fixes will have downsides that will again need to be addressed in the future (Shellenberger & Nordhaus, 2011). Technological innovation is, after all, how we have historically dealt with many of our problems. Agricultural technology feeds a population today twice as large as we had in 1968, when Paul Ehrlich famously and erroneously predicted that the world would face a catastrophic global famine in the 70s or 80s. Ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons were displaced by newer compounds that were themselves problematic contributors to climate change, but these have since been displaced by yet another generation of new compounds. In this class, we spend several days building up the logic of one of these arguments before we perform a collective about-face and consider the other. All the while I am in the enjoyable position of being the devil’s advocate, challenging whichever set of ideas the class seems most amenable to.

"In this class, we spend several days building up the logic of one of these arguments before we perform a collective about-face and consider the other. All the while I am in the enjoyable position of being the devil’s advocate, challenging whichever set of ideas the class seems most amenable to."

Critical thinking about technology means an ability to see beyond the simplistic notions that technologies and innovations are either inherently benign or inherently problematic. We as a society make active decisions that shape the future of technological innovation, yet we imagine that technologies somehow unfold in directions over which we have no potential influence and that it is up to consumers to knowingly embrace or reject technologies when they reach the marketplace. Achieving just and sustainable futures requires that we foster the ability to critically think and engage with the processes and institutions that produce and shape novel technologies. In addition to technology, students in Environmental Governance grapple with capitalism as the cause of and/or solution to environmental problems. And this year we are taking on contested ideas of what conservation of species and ecosystems should look like, given that ecologists now recognize that ecosystems can by dynamic when left to their own devices, and anthropogenic drivers are further changing the temperature and precipitation patterns the world over.

A recent survey of environmental studies syllabi found that sampled courses rarely present more than one viewpoint on issues such as these (Kennedy & Ho, 2015). To the extent that we allow students to graduate without realizing the multiple legitimate perspective on these issues, we are poorly preparing them to deal with the real world. My goal is that by the end of the class, students come to recognize that genuine contribution to policy dialogues requires subtlety and nuance. “Technology,” I hope they recognize, is too-broad a category to have a meaningful conversation about. Some technologies have devastating impacts on justice or privacy. Some, like recently the recently developed CRISPR-CAS9 genetic editing technologies, will likely have profound and widespread impacts on society (Jasanoff, Hurlbut, & Saha, n.d.). I would argue that we are ill-equipped to have meaningful dialogues about science and technology in part because we do not teach these issues with subtlety and nuance.

"To the extent that we allow students to graduate without realizing the multiple legitimate perspectives on these issues, we are poorly preparing them to deal with the real world. My goal is that by the end of the class, students come to recognize that genuine contribution to policy dialogues requires subtlety and nuance."

In both courses, I seek to create space for students to develop their ideas by modeling that there are multiple – if occasionally mutually incompatible – ways of understanding most policy dilemmas. I challenge students to test the limits of their arguments and encourage them to do the same for their peers. These goals require that my courses are heavily discussion-oriented. I ask a lot of questions, and my students ask questions of me and of their peers.

Treating these issues as open to discussion necessitates that I surrender some control over class content to my students. Each day I prepare an agenda of content that I want to cover, but as often as not the discussion takes us in an unanticipated direction. I am almost always okay with that outcome, since it usually occurs when students are interested in trying to understand how class content relates to and can help us to understand current events.

I know that students are thinking critically when they can successfully utilize class content to understand and articulate the nature of the conflicts that lie just below the fact-flinging debates that constitute modern political dialogue. To develop that skill, I bring current events to class and ask students to engage with them based upon class content. We push one another to apply content and concepts to understand the coverage of the issues in the media and the conversations that they experience in the halls of campus. Similarly, for assessments I ask students to write essays that either complicate common understandings of an issue or that utilize class concepts to make sense of current events.

My goal for my students is that they are prepared upon graduation to navigate contemporary policy processes. I work to foster critical self-awareness of their own positions as a prerequisite to an ability to understand what motivates other actors in policy dialogues. Critical thinking serves another goal as well: Genuine learning means being open to modifying our prior notions of the world. My goal for myself is that I remain open to new ideas and approaches. Perhaps more than anything, this is what I try to model for my students.

References

Collingridge, D., & Reeve, C. (1986). Science Speaks to Power: The Role of Experts in Policy

Making. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Denworth, L. (2008). Toxic truth: a scientist, a doctor, and the battle over lead. Boston: Beacon Press.

Jasanoff, S., Hurlbut, J. B., & Saha, K. (2015, April 7). Human genetic engineering demands more

than a moratorium. Retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2015/apr/07/human-genetic-engineering-demands-more-than-a-moratorium

Kahan, D. M., & Braman, D. (2006). Cultural Cognition and Public Policy. Yale Law & Policy Review,

24(1), 149–172.

Kennedy, E. B., & Ho, J. (2015). Discursive diversity in introductory environmental studies. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 5(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0245-9

Kessler, R. (2013, March 28). Long Outlawed in the West, Lead Paint Sold in Poor Nations by Rebecca Kessler: Yale Environment 360. Retrieved April 25, 2013, from http://e360.yale.edu/feature/long_outlawed_in_the_west_lead_paint_sold_in_poor_nations/2633/

Markowitz, G. E., & Rosner, D. (2013). Lead wars: the politics of science and the fate of America’s children. Berkeley : New York: University of California Press.