INNOVATIVE TEACHING SHOWCASE

Engaging Students in Large Classes

Over the past few years, many universities have experienced funding cutbacks as a result of the global economic slowdown. One technique for dealing with these cutbacks has been to reduce the number of sections taught (and thus number of instructors) by increasing the size of each section. This is less than ideal, but it must be reconciled with our desire to teach effectively. I have been teaching large classes since 1993. These sections have had enrollments between 150 and 500 students. During that time, I have gathered a number of strategies and techniques for teaching content to Introductory Psychology students, many of which could be used or adapted by other disciplines whose courses have grown in size.

My Teaching Philosophy

Most teachers will tell you that their teaching has changed throughout their career. These changes occur as a response to various pressures, including those created by students, the university, the curriculum, and those that teachers impose upon themselves. In my opinion the best teachers can recognize these pressures and use them to change their teaching for the optimal benefit of all.

It is my belief that the best learning happens when students realize that what they are learning is important. Without the investment of the student, it is difficult to instill learning beyond the most superficial levels. Psychology as a discipline is particularly well-suited to this, because most of the content discussed in class relates directly to things that students have experienced.

One view of how to treat students is as if they were consumers of education. This proposal is sometimes put forward by students who believe they should have some say in what they should be required to learn. Faculty members are often resistant to this concept and, rightly so - curriculum should never be student-driven. I believe, however, that both sides of this argument should be considered. The resolution is to tap into students' consumer attitude and present important material in a format that leads them to obtain information that they feel is useful. The secret, then, is to make sure that what students feel is useful is what the instructor knows is useful.

Engaging students as "consumers" is particularly important when working with large classes. It is very easy for students to lose attention in large lecture theaters with a droning instructor. Even if an instructor is engaging, it is still difficult to maintain complete attention. One analogy suggested is that attention in a large class is like the lights on a Christmas tree: at any given time, some lights are on and some are off. We are left with two strategies for conveying our information: 1) video clips, and 2) in-class demonstrations. These are not mutually exclusive.

Strategies for Engaging Attention: Video Clips

If class attention is like a blinking Christmas tree, we need to expose the information in a way that all the lights receive it at one point or another. This is simple: we repeat things; however, it is not sufficient to say things over and over. Rather, we must repeat things in different ways. A simple example is presenting an image associated with the particular topic being discussed, but this has a limited engagement factor. Instead, I often use short video clips to convey an idea. These clips sometimes come from YouTube or some similar source, or from materials provided by publishers. I feel that these videos should be relatively short, usually 2-5 minutes. I think of these as "dynamic overheads"— a quick way of demonstrating a concept. They should not take over the class presentation. What follows are two examples that have been useful in my classes:

- Explaining Depth Perception using a Video Clip: Wii Head Tracking (available on YouTube)

I use this video while talking about how we perceive depth. More specifically, this video represents the importance of head motion in the perception of depth. This video has all the qualities useful for my class: it is short, it provides a description of something the students will be familiar with (Wii), and it is an impressive demonstration of the concept. - Explaining Obedience using a Video Clip: Milgram Experiment (available on YouTube)

This is a replication of the classic Milgram social psychology experiment. In this clip, participants are led to believe that they are providing increasingly dangerous electrical shocks to another participant. Of course, all of this is staged, but many participants deliver seemingly fatal levels of shock, merely because they are told to do so. This video is longer than the typical 2-5 minute presentations, but it is worth showing the whole segment to demonstrate the progression of events in this study. One aspect of this video that is useful is that it is relatively contemporary. There is a classic video of this experiment that was filmed in the early 1960s in black and white. In using the more recent color version, I believe the video has a much greater impact on the typical undergraduate student.

One limitation of using online video content is that it can sometimes disappear or move. If possible, download the video directly from the source if that is enabled, or contact the content author to determine whether he or she would be willing to send you the video in a format you can store on your computer.

Strategies for Engaging Attention: In-class Demonstrations

The second strategy for engaging students is to use in-class demonstrations. To be effective, these demonstrations must have a high probability of working well. In some disciplines, this is fairly easy - demonstrating the effects of collisions on a frictionless surface always gives the same results. In psychology, demonstrations can sometimes be overly complex or so subtle that they don't really work in a large classroom.

Explaining Research Design using an Interactive Demonstration

I use this demonstration on the first day of class for two reasons. First, it allows me to introduce some concepts in research design. The students are unaware of which bottle contains which soda, as is the student volunteer. This is an example of a double-blind study. Since only a subset of students is chosen, we have also demonstrated sampling. I refer back to this demonstration a number of times throughout the course.

The second purpose is to introduce the students to an online discussion board available at Western Washington University. As part of this exercise, I ask all the students in the class to post an item to the online discussion forum indicating what limitations exist in the research design. Many students point out, for instance, that the sodas are always presented in the same order (demonstrating the order effect). This also leads the students to see what resources are available on their course website.

Explaining Color Perception using an Interactive Demonstration

One of my favorite demonstrations is the "Big Spanish Castle Illusion" (see: http://www.johnsadowski.com/ big_spanish_castle.php) which demonstrates a phenomenon called the negative color afterimage. Students stare at a reverse-colored picture of a castle for about a minute. Then, a grayscale image of the same castle is presented. As a result of staring at the reverse-colored picture, this grayscale version now appears to be correctly colored. This demonstration is so amazing, that I have to be careful to ensure that the students are actually learning something, rather than just being amused.

I use this demonstration for two purposes. First, it provides an excellent example of the negative color afterimage illusion - staring at one color leads to the illusory perception of other colors. Second, it allows me to demonstrate the role of the brain in how we perceive. There is no color in the grayscale picture, but we see it anyway. Where does this color come from? The brain.

Video Clips and Demonstrations: Conclusions

As mentioned earlier, an important purpose of the use of videos and demonstrations is to maintain the attention of students. These also allow information to be conveyed in a manner different from the classic, droning lecture. Perhaps most importantly, though, is the ability of students to take ownership of material through these techniques. If a student has participated in a demonstration, they now own the information. They can give this to someone else (I often tell them to "show it to their friends and neighbors"). In so doing, students increase the depth of processing they have committed to learning the material, which leads to better learning.

Big Classes: Logistics

In conducting a big class, half the battle is just getting things to work. Among the problems that I have faced, the logistics of disseminating information and conducting exams are prominent. Often times, these processes can take up too much valuable class time.

Disseminating Information to Large classes

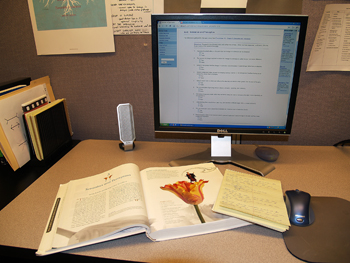

An obvious example of the usefulness of technology is using the Internet for information dissemination. For many instructors, the primary portal for providing online interactions with students are pre-fabricated websites created by applications like "Blackboard" or "Moodle." Blackboard has become highly integrated into my class. Like many instructors, I post PowerPoint files, answer questions, post grades and provide supplementary study aids through this venue. Even something as simple as posting the course syllabus to Blackboard has logistical advantages. Passing out paper copies of the syllabus is time-consuming and distracting. Describing the key points of the syllabus using a few PowerPoint slides reduces this annoyance and allows the students to follow more closely.

Posting information through a venue such as Blackboard has many advantages:

- It saves departmental resources, such as paper supplies.

- Students are accustomed to the format.

- Students know where to find materials. On occasion, I have had students request material be posted to Blackboard as opposed to paper copies, because that way they know where to find it.

- It helps them learn. Some students have commented on their evaluations that the use of web technology is a very useful component of their learning. (See comments.)

Using Online Exams

Conducting an exam with a class of 400 students requires military precision. An entire 80-minute class must be devoted to conducting the exam. In the class time I have available, I have to distribute the exam, seat the students (while placing their packs and books at the front of the class), give the students 60 minutes to complete the exam, collect the exams and ensure that the answer sheets have been correctly filled. This works well, as long as nothing goes wrong. One time I was short 20 exams. Things did not work well that day.

Online Psychology Exam / © Ian Couch, 2010

Recently, I have experimented with the use of online exams as a means of reducing some of the logistical headaches of in-class exams. These are multiple choice exams conducted through the Blackboard system. These exams can be created within Blackboard, but I usually use software made available by my textbook representative. I typically create a 60-item test and give students 1 hour to complete it. They can begin the test at any time they choose, within a 24-hour period. For my tests, once it is completed, it cannot be taken again. All of this is programmable through Blackboard.

Online testing has a number of advantages. First, it allows for the quiz to occur outside of class time, giving me more time to teach material. Second, the students can receive instant feedback, as the scoring is done by Blackboard directly. Third, as mentioned earlier, this is something to which students are accustomed. They have been "trained" by the myriad of online "intelligence" and "personality" tests.

However, there are some obvious problems with this exam format. In my first foray into an online exam, the mean was comparable to an in-class exam for an introductory psychology class — approximately 79%. However, on the next online exam, the students had become more savvy about the process and achieved a mean score of 88%. Not surprisingly, in my class evaluations that quarter, many students commented on how much they preferred the online exams to the in-class exams. The simple moral of this story is that online exams cannot be simple replicas of in-class exams. They must consist of questions that require much greater depth of processing, as you must assume that the students have access to all of their course materials while they are taking the exam.

Online Information Dissemination and Testing: Conclusions

In keeping with rapid changes in technology, the use of online technologies for large classes has become increasingly important. Students are familiar with these technologies which provide a way to reduce logistical complexities for large classes. With increased financial pressures on universities, online resources will become increasingly important. There is some talk of creating "hybrid" courses at Western Washington University. These will merge online courses with in-class courses, hopefully providing the best of both of these worlds. These courses are already taught at many universities and are an important model to consider.

Big Classes: Low Stakes Writing

With classes of 400, assessment is usually limited to multiple-choice exams. Short answer questions can be used, but it is only feasible with considerable teaching assistant support. At Western Washington University, TA support for introductory psychology is limited or non-existent. It is possible however, to broaden assessment, even with limited TA support.

Typically, I augment my multiple-choice exams with a series of "low-stakes" writing assignments. These are assignments that count in a minor way towards the final grade, but for which no feedback is provided (because of the lack of TA support). The assignments involve reading chapters from a reader and answering a set of questions for each chapter. A senior student (usually helping me in exchange for course credit) reads each submission and, if it is not merely a grocery list (i.e., an honest attempt), provides them with a single point.

The purpose of these assignments is twofold. The chapters in the readers are "lay-person" descriptions of a concept discussed in class (e.g., the use of operant conditioning in training whales). Thus, they allow the students to see that the concepts apply in the real world. Secondly, the opportunity to do some writing, even with limited feedback, is an important part of getting students to become stronger writers later in their academic careers. When they write their course evaluations, students often comment that they enjoyed completing this assignment. They sometimes even suggest that more of the course readings were like those in their readers. One has to be careful with these assignments, however. It is easy for a student to provide non-answers to their assignments, which can be missed by an overworked senior student. Despite this, I believe that these assignments can be a useful component of a large lecture course.

A Concluding Note

Teaching large classes has become an unavoidable reality that is not going away anytime soon. My experience has been that many of the drawbacks of a large class can be ameliorated with some creativity. Many of the techniques described here were obviously developed for teaching introductory psychology. Many of the basic ideas can be implemented outside of this particular discipline. The use of video clips is particularly suited to the social sciences, but the interactive demonstrations suit the natural and physical sciences. Further, much of the discussion of online technological enhancements is relatively discipline free.

Early in my career, the primary motivator for my teaching was to get through any given lecture without appearing to be an idiot. My hope is that, with experience, this has changed. One of the most important things I have learned in improving my teaching is using the students' desires and proclivities as a lever to improve their own learning. Obviously, we should never pander, but given what we know about the nature of learning in large groups, we should adapt to this format to the best of our ability.